|

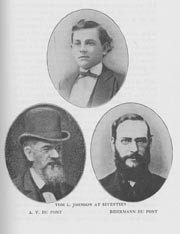

II THE MONOPOLIST MADE It was the first of February, 1869, that I went to Louisville to take my job in the rolling-mill and it was at about this time that Bidermann and Alfred V. du Pont bought a street railroad in Louisville. These brothers were the grandsons of Pierre Samuel du Pont, one of the physiocratic economists of France, associate of Turgo, Mirabeau, Quesnay and Condorcet to which group "and their fellows" Henry George inscribed his Protection or Free Trade, calling them "those illustrious Frenchmen of a century ago who in the night of despotism foresaw the glories of the coming day." Pierre du Pont, after narrowly escaping the guillotine, came to this country during the reign of Terror and established on the Brandwine the du Pont powder works known as the E. I. Du Pont de Nemours Powder Company, the concern that now manufactures practically all the high explosives in the United States. The du Ponts were friends of our family and gave me an office job in connection with their newly-acquired street railroad. I lived with the family of my uncle Captain Thomas Coleman in Louisville and a lively family it was with its nine daughters and two sons. Though these girls were my cousins and I was but fifteen years old I fell in love with one after another of them until I had been in love with all except the few who were either too old or too young. The associations of this home and the influence of that splendid woman, my aunt Dullie Coleman, and her daughters saved me from the temptations that ordinarily beset the country boy in the city. My salary was seven dollars a week and my duties were varied. I collected and counted the money which had been deposited by the passengers in the fare-boxes, made up small packages of change for the drivers ( the cars had no conductors), and in a short time took entire charge of the office as bookkeeper and cashier. I sat up until eleven o'clock every night for a month learning to "keep books." At the end of that time a trial balance had no terrors for me. This was of course before the introduction of electricity in street railway operation and the cars were drawn by mules. How I hated to see horses and mules go into the street car service where they would be ground up as inevitably, if not quite as literally, as if put through a sausage machine! It was this feeling of pity for the defenseless creatures that first interested me in cables and electric propulsion. From the very first it was the operating end of the business that appealed to me. My liking for mechanics was stimulated by my environment and I was soon working on inventions, some of which I afterwards patented. From one of these, a fare-box, I eventually made the twenty or thirty thousand dollars which gave me my first claim to being a capitalist. The fare-boxes in use up to that time were made for paper money. Mine was the first box for coins, paper currency having just been withdrawn from circulation. It held the coins on little glass shelves and in plain sight

until they had been counted. Since any passenger as well as anyone acting as a spotter could count the money there wasn't much likelihood that either the drivers or the car riders would cheat. This box is still in use. In a few months I was secretary of the company, and at about the end of my first year of employment my father came in from the farm and the du Ponts made him superintendent of the road. He continued in this position until he was appointed chief of police of Louisville, several years later. Then I became superintendent, holding the job until 1876 when I embarked in business for myself. I may say, with all propriety, that Bidermann du Pont, the president of the road, found in me a hard working and efficient assistant, but I cannot say that I never occasioned him any anxiety, for my restless, eager nature was constantly seeking ways of expression-which ways were not always either dignified or safe. For instance, one night when a lot of our cars were lined up on Crown Hill, waiting to carry the crowds home from a late entertainment in a summer garden, I challenged the drivers to join me in taking one of the cars down the hill as fast as it would go. The plan was-to start a car with as much speed as the mule team could summon, when it was fairly started the driver to drop off with the team, the rest of us to stay on for no reason in the world except to see "just how fast she would go." The drivers weren't very keen to accept my challenge, but finally four of them decided to do so. After several starts we got up a rate of speed rapid enough to suit us and away we went. As the car tore madly down the hill I recalled the railroad track at the bottom and the curve in our track just beyond but there really wasn't time to think about what might happen if the car and a train should reach the crossing at the same instant; for just then we shot over the railroad track, hit the curve which didn't divert the car from its straight course, and landed half-way through a candyshop. The company paid damages to the shop-keeper, and what Mr. du Pont thought of the episode I never knew for even after the matter had been adjusted he never mentioned it to me. A little while after this when there were some new mules in the stables waiting to be trained to car work, I decided to hitch the most refractory and unpromising team to a buggy and "break them in.: A little driver named Snapper joined me in this enterprise. With much difficulty, and the assistance of some dozen darkeys, we got the mules into harness and hooked up to an old, high seated buggy. I had the reins, Snapper took his place on the seat beside me and we were off. It wasn't long before I knew to a dead certainty that those mules were running away. We had a clear stretch of road before us, however, and I reflected that they'd have to stop sometime and trusted to luck that we'd be able to hang on until they did. But presently, just ahead of us, there appeared a great, covered wagon, with a fat, sun-bonneted German woman on the seat driving. She was jogging along at a comfortable pace, all unconscious of the cyclone which was approaching from behind. To get around her wagon was impossible, but here was my chance to stop our runaway! I steered the mules straight for the wagon, one on one side, one of the other, and the pole of the buggy caught the wagon box fairly in the middle. In the mix-up Snapper and I fell out, the mules dashed on with some remnants of the wreck still attached to them, and the old lady was the most surprised individual you every saw in your life. She wasn't hurt, and neither were we, nor was the wagon much harmed. The president of the road was as silent on this foolhardy adventure as he had been on the candy-shop scrape, but Mr. Alfred du Pont took me severely to task for it, saying that while he did not object to my breaking mules he did object most seriously to having me break my neck. I had not been in the street railroad business long before I determined to become an owner. I didn't want to work on a salary any longer than I could help. My fondness for girls in general and girl cousins in particular culminated in my marriage, October 8, 1874, to a distant kinswoman of my own name, Maggie J. Johnson, when she was seventeen and I was twenty. At twenty-two I purchased the majority of the stock of the street railways of Indianapolis from William H. English, afterwards candidate for vice-president of the United States in the Garfield-Arthur and Hancock-English campaign. I went to Indianapolis to see Mr. English in the hope of interesting him in my fare-box. He said to me, "I don't want to buy a fare-box, young man, but I have a street railroad to sell." My business dealings with him were so unpleasant and the charges which my lawyer (afterwards Governor Porter of Indiana) brought against him in a law suit so severe, that the petition embodying them was used by his Republican opponents as a campaign document. That fight with Mr. English was my first great business struggle, and it was a fight for a privilege-for street railway grants in the city of Indianapolis. I had some money ,but not enough for my purchase. Mr. Bidermann du Pont, thought he had no faith in my business associates and though the road was in a badly demoralized state, loaned me the thirty thousand dollars I needed with no security whatever except my health, as he himself expressed it. That loan meant a lot to me, but the confidence which went with it meant more, for Mr. Du Pont was the first business man to give me any encouragement. When I made my final payment to him some five or six years later I told him that my money obligation was now cancelled, but that a life-time of friendship for him and his could not discharge my greater obligation for his faith in me. My father went with me to Indianapolis and became president of the company. When a friend asked him: "If you are president of the road, what is Tom?" he replied, "Oh, Tom's nothing! He's just the board of directors. As this board of directors, I speedily realized that our enterprise would be a failure unless we could free ourselves from Mr. English's persecutions. He was old enough to be my father, and his attitude towards me was arrogant. He was the most influential man in Indianapolis and not above threatening us with his power over the city government unless we cooperated with him in every way, especially in getting tenants for his houses of which he owned about two hundred, and which he rented to employes of our road and to other workingmen. Mr. English was a typical representative of the powerful agent of special privilege of that day. He was president of one of the principal banks of the city. The people's money goes into the banks in the form of deposits. The banker uses this money to capitalize public service corporations which are operated for private profit instead of for the benefit of the people. How incongrous that the people's own savings should be used by Privilege to oppress them! Mr. English's great asset was his domination of the local city government through which he controlled the taxing machinery of the city, thereby keeping his own taxes down at the expense of the small tax-payer. When I bought into the railroad he turned the office of treasurer over to me as his successor and at the first meeting of the board of directors we passed resolutions stating that his account had been audited and giving him a receipt for his stewardship. When I objected to this because I had not seen the books he said it was a mere matter of form and that he would turn them over to me immediately after the meeting. It was eleven months before I ever got a look at those books and then my right to them had been established by a lawsuit. After going through the books I forced Mr. English to make several restitutions of very large amounts of money to the company. Once we had a disastrous fire and he immediately notified the insurance companies that the damages must be paid to him. We had to consent to this or expose ourselves to expensive and annoying litigation. He kept us in constant hot water. We had paid ten per cent. of the purchase price in cash and given notes running through a period of ten years for the remaining ninety per cent. His reason for selling to us in the first place seems to have been to rid himself of some partners who he did not like. He evidently expected to make us very sick of our bargain, to benefit by whatever payments we made and finally to get the property back into his own hands unencumbered by undesirable partners. I did not propose to be frozen out in this manner, however, and was able to borrow enough money from F. M. Churchman, an Indianapolis banker, to purchase our own notes at fourteen cents on the dollar. It happened that Mr. Churchman was not on friendly terms with Mr. English and was the more willing on that account to help me. He and his friends were interested in the gas company and were familiar with the business possibilities of public service corporation. He seems impressed with my ability to make the railroad pay which, by economy and careful management, it soon commenced to do. We never felt quite safe from Mr. English even after we have paid him off and had acquired the minority stock, but in Mr. Churchman and his friends we had strong and influential allies. As I look back on those days now there seems to have been no limit to my energy, my ambition, or my capacity for hard work; but then, as in all my later life, I took a great deal or recreation. I couldn't have worked so much, if I had played less. I was fond of baseball, billiards and horseback riding and bicycling and automobiling were to come in their time; but after all I loved my work more than anything else, especially the mechanical side of it-the experimenting and inventing-and that was really my greatest recreation.

|